Aging is a natural, inevitable part of life—but the idea that mental deterioration is a normal part of aging is only partly true. While some degree of slowed information processing is expected as we grow older, significant cognitive decline isn’t a foregone conclusion. In fact, many people maintain high levels of cognitive function well into their later years, challenging the belief that cognitive loss is simply unavoidable. What some elders do not lose—despite age—are the foundational aspects of brain function, such as language, accumulated knowledge, and long-term memory. This reality raises a powerful question: how do we support cognition and memory problems that do arise, and more importantly, how can we preserve or even enhance brain health as we age?

You may also like: How to Choose the Best Brain Supplements for Adults: Science-Backed Ingredients That Support Focus, Memory, and Mental Clarity

Understanding how to improve cognitive function in elderly individuals requires an exploration of both the biology of aging and the scientific strategies that support neural vitality. From lifestyle interventions and nootropic support to nutritional choices and mental stimulation, research offers promising avenues not only to reduce the loss of cognitive function but also to potentially reverse cognitive impairment when caught early. Whether you’re caring for an aging loved one or seeking proactive strategies for your own mental longevity, understanding the causes of cognitive decline and the tools to counteract them is essential for navigating the later decades of life with clarity and purpose.

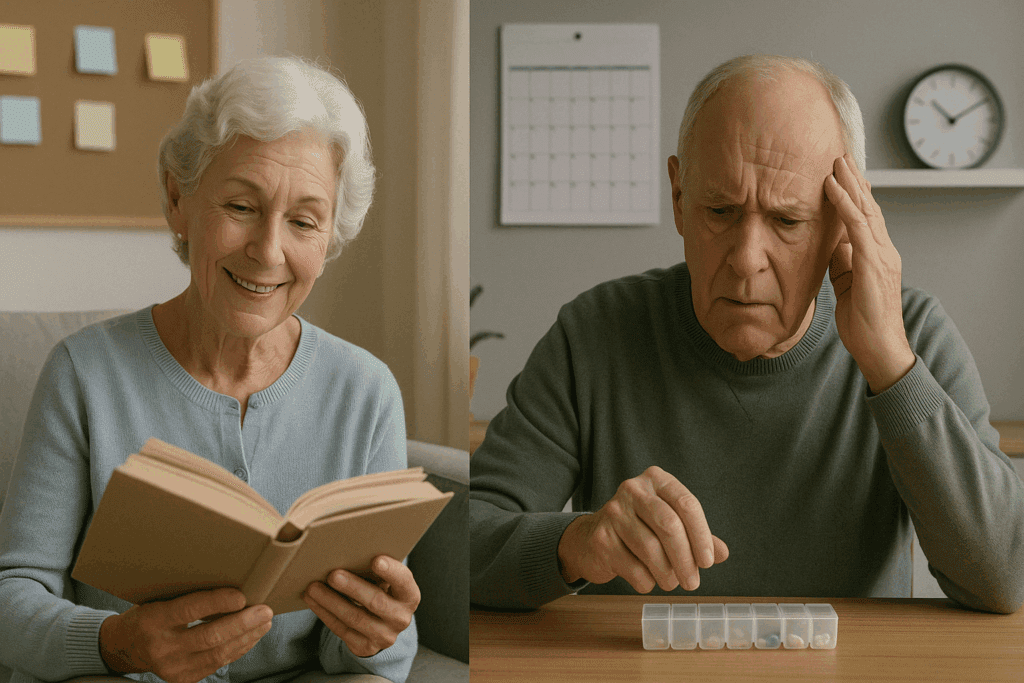

Distinguishing Normal Aging from Mild Cognitive Impairment

Not all cognitive changes in the elderly signify disease. Some aspects of brain function naturally slow down with age. This includes reduced processing speed, minor memory lapses like forgetting names temporarily, or needing more time to learn new skills. However, when changes in memory, reasoning, language, or judgment begin to interfere with daily life, they may signal a more concerning condition known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The distinction between MCI and normal aging is critical, as the former can be a precursor to more severe cognitive deterioration such as dementia or Alzheimer’s disease.

Mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging is a nuanced topic. While occasional forgetfulness might be brushed off as benign, a consistent pattern of forgetting important events, struggling with familiar tasks, or exhibiting behavioral changes may indicate lower cognitive ability that deserves clinical attention. A person experiencing cognitive and memory problems should undergo a formal assessment to determine whether the symptoms fall within the range of expected aging or reflect early signs of a deeper issue. Recognizing this difference early on provides a vital window for intervention, as certain types of cognitive impairment can be slowed or even improved with the right strategies.

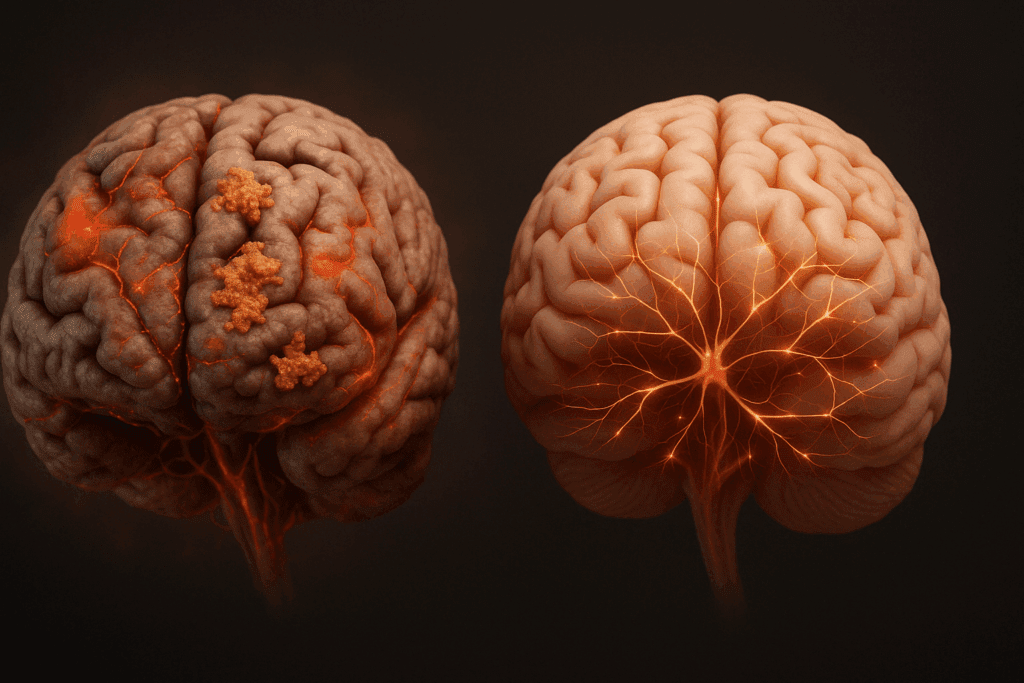

The Biological Underpinnings of Cognitive Decline

Understanding the underlying mechanisms that drive cognitive deterioration is essential for identifying effective prevention and treatment. Aging impacts the brain in multiple ways, including the reduction of gray matter volume, decreased blood flow, and the buildup of harmful proteins like beta-amyloid plaques. These biological changes affect synaptic connectivity, disrupt communication between neurons, and reduce the brain’s ability to repair itself—all of which contribute to a gradual decline in cognitive function.

One of the most insidious contributors to elderly cognitive decline is chronic inflammation. Age-related inflammation, often referred to as “inflammaging,” can accelerate neurodegeneration and impair memory formation. Additionally, oxidative stress damages brain cells through the accumulation of free radicals, further compromising cognition. These physiological changes underscore why some older adults experience cognitive loss more severely than others. It also explains why cognitive problems causes may vary from vascular conditions and chronic illnesses to genetic predispositions and environmental exposures. Fortunately, these insights have led to the development of science-backed interventions that can delay or even reverse some aspects of decreased cognitive function.

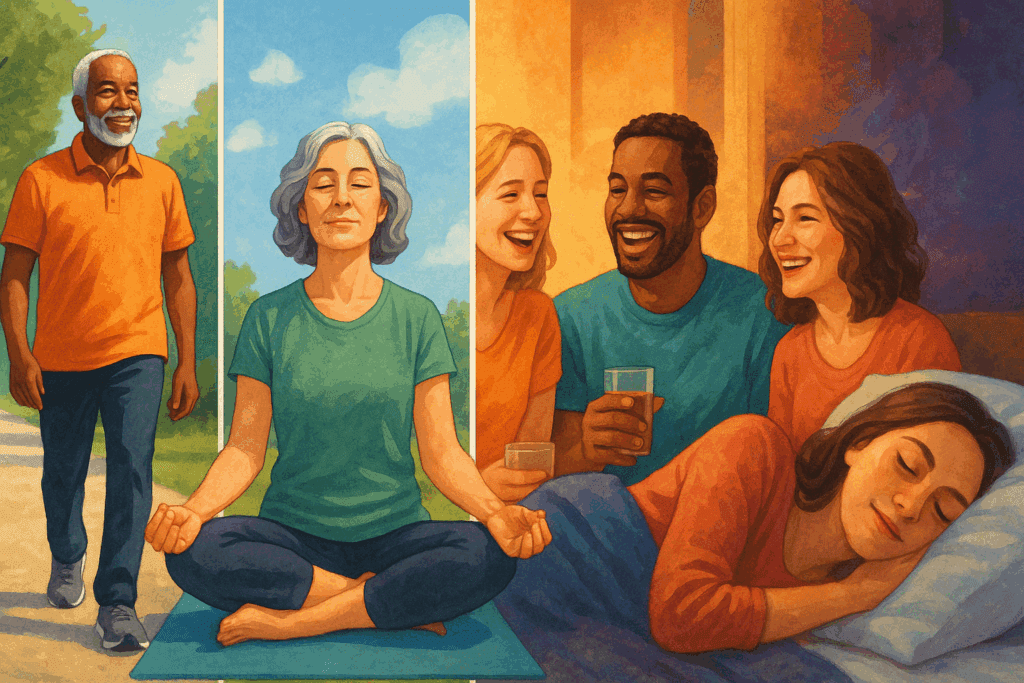

Lifestyle Choices That Affect Cognitive Health

The connection between lifestyle and cognitive performance is one of the most thoroughly studied areas in aging research. Physical activity, for instance, has been shown to improve brain function by increasing blood flow, enhancing neuroplasticity, and boosting the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein essential for learning and memory. Regular aerobic exercise not only supports cardiovascular health but also helps combat cognitive decline aging by keeping neural circuits active and adaptable.

Sleep quality is another critical factor that affects cognitive ability. During deep sleep, the brain clears out waste products, including those associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Poor sleep hygiene, especially in older adults, can lead to disruptions in memory consolidation and executive function. For elders reporting they’re not cognitive enough to understand daily tasks or interactions, improving sleep may be a foundational intervention. Similarly, chronic stress—often underestimated—can harm the brain by increasing cortisol levels, shrinking the hippocampus, and impairing attention and memory. Stress management strategies such as meditation, mindfulness, and social engagement serve as powerful tools to counteract these risks and support better mental function in older age.

Nutritional Strategies to Support Brain Function

Diet plays a pivotal role in brain health, offering one of the most accessible ways to reduce cognitive decline and promote longevity. Nutrient-dense diets like the Mediterranean or MIND diet—rich in leafy greens, berries, olive oil, and fatty fish—are associated with slower cognitive decline and a lower risk of developing dementia. These diets provide essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants that combat oxidative stress and reduce inflammation in the brain.

B vitamins, particularly B6, B12, and folate, are critical for cognitive health due to their role in homocysteine regulation, a compound linked to brain atrophy when elevated. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in salmon and flaxseeds, support neuronal integrity and have been shown to improve memory and focus. Deficiencies in key nutrients can lead to cognitive deterioration that is often mistaken for normal aging. In such cases, correcting the deficiency can reverse the loss of cognitive function, a clear demonstration that not all cognitive loss is permanent or inevitable. Furthermore, staying hydrated and minimizing sugar and processed food intake are simple but impactful changes that support healthy cognition and reduce inflammation that may affect cognitive performance.

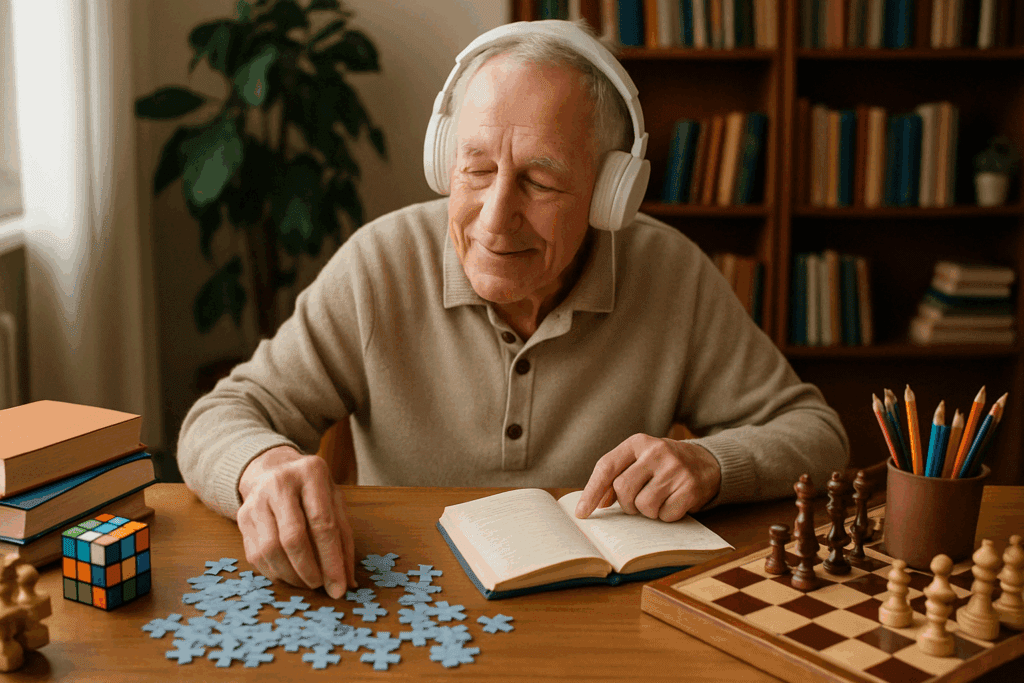

Cognitive Training and Mental Stimulation

One of the most effective, non-pharmacological approaches to improving cognition in older adults is cognitive training. This includes a wide range of mental activities that challenge memory, reasoning, attention, and executive function. Activities like learning a new language, playing musical instruments, solving puzzles, or engaging in strategy games such as chess stimulate brain plasticity and strengthen neural networks.

Contrary to the belief that cognitive deterioration is irreversible, targeted cognitive training programs have shown promise in enhancing mental function even in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. By challenging the brain in novel ways, these interventions may slow mental decline and help preserve decision-making ability and independence. In fact, studies have demonstrated that even short, regular sessions of brain training can lead to lasting improvements in reasoning and processing speed. This raises an encouraging possibility: cognitive loss does not have to be permanent, and in some cases, treatment for cognitive impairment that includes structured mental engagement can restore function.

Social Interaction and Its Impact on Mental Decline

Social connection is more than just a source of emotional support—it is also a potent defense against decreased cognitive function. Older adults who maintain strong social networks tend to exhibit better memory, less cognitive decline, and lower rates of dementia. Human interaction stimulates the brain, encourages conversation, and often involves the kind of problem-solving and emotional regulation that keep cognition sharp.

Isolation, on the other hand, can accelerate cognitive deterioration. It contributes to depression, disrupts sleep, and may increase the risk of dementia by as much as 50%. For elders who seem not cognitive enough to understand causing harm to others or themselves, it is often the absence of meaningful relationships and mental engagement that drives such changes. Encouraging community involvement, intergenerational relationships, and volunteer activities can serve as both protective and therapeutic strategies. Regular interaction keeps the mind engaged and reinforces the sense of identity, purpose, and agency—critical components in maintaining brain health as we age.

Addressing Medical Conditions That Influence Cognitive Function

Many medical conditions contribute to or exacerbate cognitive changes in the elderly. These include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, thyroid disorders, and even untreated infections or medication side effects. Vascular dementia, for example, is often linked to poorly controlled hypertension and strokes. The relationship between cognition and dementia is not always straightforward; while dementia is a clear form of cognitive deterioration, subtler cognitive and memory problems may arise from other modifiable conditions.

Depression in older adults often mimics dementia, creating a phenomenon known as “pseudodementia,” where symptoms of cognitive decline resolve with effective treatment. Therefore, identifying and managing coexisting medical issues is crucial in determining whether cognitive loss stems from an underlying condition that can be treated. For many patients, addressing these root causes—through medication adjustments, lifestyle changes, or targeted therapies—can dramatically improve cognitive and decision-making ability.

Pharmaceutical and Nootropic Interventions

While lifestyle changes are foundational, there are also pharmacological and supplemental approaches that can support elderly cognitive function. Certain medications like cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine are commonly prescribed for Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. These drugs work by enhancing neurotransmitter availability and improving synaptic communication, though they are not a cure and offer varying results.

Nootropic supplements are gaining attention for their potential to enhance focus, memory, and clarity without the side effects of prescription drugs. Compounds such as citicoline, phosphatidylserine, and L-theanine have shown promise in reducing cognitive decline aging symptoms and supporting long-term brain health. While more research is needed, early studies suggest that targeted supplementation can improve focus and mood in older adults experiencing early signs of cognitive decline. However, it’s important to consult a healthcare provider to ensure these substances are safe and appropriate for each individual’s health profile, especially when other conditions or medications are involved.

Can Cognitive Decline Be Reversed?

One of the most common and pressing questions posed by caregivers and patients alike is this: can cognitive impairment be reversed? The answer depends on the cause, severity, and timing of the intervention. In cases where cognitive loss is driven by medication side effects, nutritional deficiencies, or unmanaged chronic conditions, function can often be restored once the root issue is addressed. This kind of cognitive rebound is not only possible but well-documented in clinical settings.

When it comes to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, complete reversal is unlikely. However, slowing the progression of symptoms and improving quality of life through a multifaceted approach remains a realistic and scientifically supported goal. The question of how to stop cognitive decline becomes one of identifying risk factors early and applying preventive strategies consistently. Whether through exercise, diet, social engagement, or supplementation, the cumulative effect of small daily actions can add up to meaningful protection against cognitive deterioration.

Why Is My Cognitive Function Declining?

For many individuals, the realization that their memory or attention is slipping comes gradually. Questions like “Why is my cognitive function declining?” reflect not just concern but also a desire for answers—and empowerment. Cognitive decline can be caused by a variety of factors, including genetic predisposition, cardiovascular issues, chronic stress, inflammation, poor sleep, and exposure to toxins. It may also be a result of aging-related hormonal changes or reduced neurogenesis in the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center.

Importantly, not all decline is pathological. Cognitive changes in the elderly may simply reflect a slower but still healthy brain function. However, when loss of thinking becomes disruptive to daily life, a thorough medical evaluation is essential to determine which of the following can contribute to cognitive decline in that specific case. With the right information, the path to treatment—or at least mitigation—becomes clearer, and the fear surrounding cognitive deterioration can be replaced with a sense of agency and hope.

Preserving Brain Health Across the Lifespan

Long-term brain health begins early but must be nurtured throughout life. Preventing elderly cognitive decline involves creating an environment that supports the brain’s resilience. Activities that challenge the mind, strengthen the body, and nourish the spirit are not just hobbies—they’re strategic tools for safeguarding cognition and emotional well-being. Whether you’re 40 or 80, the same principles apply: stay active, stay connected, stay curious.

By understanding the factors that affect cognitive health, recognizing early signs of trouble, and implementing targeted strategies, it becomes possible to age not just gracefully—but intelligently. Through intention and knowledge, we can reframe the narrative around aging from one of inevitable decline to one of continued growth and clarity.

Standalone FAQ: Advanced Insights on Cognitive Decline and Aging

1. Why is my cognitive function declining even though I live a healthy lifestyle?

Cognitive decline can sometimes progress even in individuals who follow a healthy lifestyle due to underlying genetic predispositions, chronic inflammation, or environmental exposures over time. Emerging research suggests that neuroinflammation, microvascular damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction may silently affect cognitive health despite a clean diet and regular exercise. In such cases, decreased cognitive function may stem from subtle neurodegenerative processes that don’t respond solely to traditional healthy habits. Moreover, certain individuals experience a loss of cognitive function due to prolonged psychological stress or unrecognized sleep disorders, both of which disrupt neural regeneration and synaptic plasticity. Understanding these deeper mechanisms is essential when exploring treatment for cognitive impairment beyond lifestyle optimization.

2. Can cognitive impairment be reversed, or is it always permanent?

While some forms of cognitive loss are irreversible—such as those caused by advanced neurodegeneration—others, especially early-stage or functional cognitive issues, may be partially or fully reversible. For example, elderly cognitive decline related to medication side effects, nutritional deficiencies (like B12 or omega-3), or untreated sleep apnea often shows measurable improvement with appropriate intervention. Mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging remains a crucial distinction here: unlike permanent cognitive deterioration, MCI often responds well to interventions like cognitive training, pharmacologic support, and lifestyle adjustments. Research in neuroplasticity also reveals that targeted cognitive rehabilitation can slow or even modestly reverse decline in cognitive function through consistent, structured mental and physical activity. However, the window of reversibility depends heavily on early detection.

3. What are the lesser-known causes of cognitive and memory problems in older adults?

Beyond well-known causes like Alzheimer’s disease or stroke, a host of underappreciated factors can affect cognition and memory in the elderly. These include chronic infections (such as Lyme disease), persistent low-grade inflammation, heavy metal toxicity, and endocrine disruptions like thyroid dysfunction. Even long-standing exposure to high cortisol levels from chronic stress can cause hippocampal shrinkage, contributing to cognitive changes and memory loss. Notably, certain psychiatric conditions—like untreated anxiety or depression—may mimic or exacerbate cognitive decline, making diagnosis and treatment more nuanced. It’s also important to investigate polypharmacy, as multiple medications often interact in ways that impair memory and executive function in aging brains.

4. Why do some elders not lose brain function while others experience rapid mental decline?

The resilience seen in elders who maintain cognitive sharpness into advanced age often reflects a combination of genetic protection, higher cognitive reserve, lifelong learning habits, and strong social engagement. Brain imaging studies show that individuals with higher education, frequent cognitive activity, and vibrant social lives build more extensive neural networks that buffer against cognitive decline aging. In contrast, those with limited mental stimulation and isolation may show earlier signs of cognitive deterioration. There’s also growing interest in epigenetics—how gene expression is influenced by lifestyle over time—which may explain why some elders do not lose brain function despite facing the same risks. These findings suggest that lifelong habits play a vital role in determining who maintains cognition into late life.

5. Which of the following can contribute to cognitive decline: dehydration, loneliness, or poor vision?

Surprisingly, all three—dehydration, loneliness, and poor vision—can significantly contribute to a decline in cognitive function, although they are often overlooked. Dehydration can cause temporary but profound cognitive fog and even mimic signs of dementia in the elderly. Loneliness, a major psychosocial stressor, is strongly linked with cognitive and memory problems due to its association with depression, inflammation, and reduced neural connectivity. Poor vision affects cognition indirectly by limiting sensory input, reducing mobility, and contributing to social withdrawal—all factors that accelerate cognitive deterioration. Recognizing these contributors offers an opportunity for prevention strategies that go beyond brain-centric treatments and address holistic well-being.

6. How do psychological factors affect cognitive changes in older adults?

Psychological conditions like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress can substantially affect cognitive performance, often presenting as memory lapses, difficulty concentrating, or slowed thinking. This form of cognitive decline isn’t always structural or neurodegenerative but rather functional and potentially reversible. Cognitive reasons for decline in this context often involve disruptions in neurotransmitter balance, especially serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine—all of which influence attention, working memory, and motivation. In some cases, individuals may be labeled as “not cognitive enough to understand,” when in fact emotional distress is masking intact reasoning capabilities. Understanding the emotional underpinnings of cognition is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and guide more compassionate, effective treatment.

7. How can caregivers identify early signs of cognitive decline before formal diagnosis?

Caregivers are often the first to notice subtle indicators of cognitive loss, which may appear as changes in routine, difficulty managing finances, new forgetfulness, or personality shifts. Unlike overt memory lapses, early signs might include increased frustration, disorganization, or avoidance of social settings. Behavioral patterns such as repeating questions, misplacing familiar objects, or making unusual financial decisions may signal early-stage cognitive problems. One concerning situation arises when an individual becomes not cognitive enough to understand causing harm to others, such as through neglecting medication or driving recklessly—requiring immediate intervention. Identifying these patterns early allows for a more proactive approach to treatment and risk management.

8. What makes mental deterioration different from normal aging?

Although mental deterioration is a normal part of aging to some extent—such as slower recall or minor forgetfulness—pathological cognitive decline is marked by functional impairment. The difference lies in impact: normal aging does not affect daily decision-making or the ability to live independently, whereas decreased cognitive function interferes with activities like cooking, managing medications, or navigating familiar environments. Mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging can be hard to distinguish, but the former shows measurable deficits on neuropsychological testing. Additionally, mental decline that progresses steadily or affects language, orientation, or complex tasks should raise red flags. Recognizing this distinction is vital for timely interventions that might delay or mitigate further cognitive deterioration.

9. How can social interaction affect cognitive decline in aging populations?

Social interaction plays a powerful role in buffering against elderly cognitive decline by stimulating multiple areas of the brain, including those responsible for language, empathy, and problem-solving. Regular engagement in meaningful conversations, group activities, or volunteer work helps maintain neural plasticity and protects against cognitive loss. Conversely, isolation and reduced communication have been associated with a faster decline in cognitive function and a higher risk of dementia. Cognitive changes in the elderly are often accelerated in socially deprived environments, making social connection a non-pharmacologic intervention of equal importance to brain-training games or supplements. Promoting social vitality is an evidence-based way to prevent or slow cognitive and memory problems in older adults.

10. What are the most promising emerging treatments for preventing or slowing cognitive decline?

Emerging strategies in preventing cognitive decline aging include personalized nootropic regimens, neurofeedback therapy, and gut-brain axis interventions. For example, synbiotic supplementation (combining prebiotics and probiotics) may reduce inflammation and affect cognitive function positively through microbiome modulation. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is also showing promise in clinical trials for enhancing memory and attention in individuals with lower cognitive ability. Precision medicine approaches—using genetic, metabolic, and neuroimaging data to tailor treatment—are expected to revolutionize how we approach cognitive decline in the next decade. Although no single intervention reverses cognitive deterioration completely, these innovations offer exciting, multidisciplinary paths for how to stop cognitive decline or at least delay its progression meaningfully.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Mental Clarity and Resilience in Aging

Cognitive decline in aging is a multifaceted challenge—but one that is far from hopeless. With the right combination of lifestyle adjustments, medical management, cognitive training, and nutritional support, we can meaningfully impact the trajectory of brain aging. From understanding the root causes of cognitive problems to exploring whether cognitive impairment can be reversed, the evidence is clear: much of what was once considered inevitable is now understood as modifiable.

Whether someone is experiencing mild cognitive impairment vs normal aging symptoms, or struggling with lower cognitive ability due to medical issues, there is a wide array of tools available. Each small change—be it eating more brain-healthy foods, reconnecting socially, or committing to mental exercises—can collectively reduce cognitive deterioration and support sharper thinking. And perhaps most importantly, we must challenge the outdated belief that mental decline is simply a fact of life. For many, what some elders do not lose is the inner spark of curiosity, resilience, and wisdom that remains fully intact when nurtured properly.

By approaching cognitive health with the same level of intention we give to physical wellness, we can ensure that the later decades of life are not just longer—but brighter, more aware, and filled with meaning. The journey to maintaining mental clarity in older age begins with knowledge, continues with action, and flourishes with hope.

Was this article helpful? Don’t let it stop with you. Share it right now with someone who needs to see it—whether it’s a friend, a colleague, or your whole network. And if staying ahead on this topic matters to you, subscribe to this publication for the most up-to-date information. You’ll get the latest insights delivered straight to you—no searching, no missing out.

Further Reading:

6 simple steps to keep your mind sharp at any age

Therapeutic approaches for improving cognitive function in the aging brain

22 brain exercises to improve memory, cognition, and creativity